A recent visit to Washington presented the opportunity to visit the Vietnam War Memorial Wall. The setting was a pleasant summer evening, under billowing thunderheads and softly fading western sunlight. I’ve had the occasion to visit the wall before, finding it as ever the most poignant place I have ever known. The black marble wall matches the color of the war on the American consciousness; an indelible stain upon the memory of posterity; a cold reminder of the uniquely human tragedy that unfolded a world away and over four decades ago.

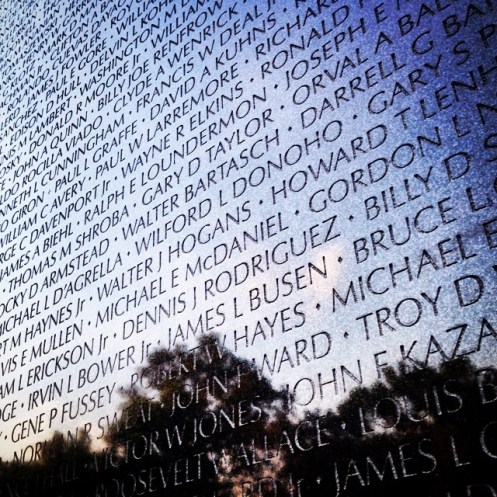

Names on the Vietnam Wall.

The placement of the memorial itself is little different. One gets the sense that the memorial, however well visited, was stuffed unceremoniously in one corner of the National Mall, as if hiding it away could make the pain of it be forgotten somehow. The Wall lacks the soaring majesty of the other memorials scattered about our nation’s capital city. The grandeur of the Washington Monument scraping the skies above is nowhere to be seen. Nor is the vista from beneath the feet of Lincoln, east across the Reflecting Pool, around the great obelisk, and on to the seat of American legislative power beneath the Capitol rotunda, apparent here. The elaborate and vaguely ostentatious King – Jefferson – Oval Office staring competition seems part of another world, a world of white marble rather than black. Instead, the Wall stands alone, on the far side of an oft-deserted bog-like park bearing the misleading title Constitution Gardens. On this visit it seemed to be inhabited mostly by geese. The query “where have all the flowers gone” seems to fit the locale. The Wall’s inherent symbolism indeed appears in the most unusual corners. However thick the crowds, this quiet corner of the Mall affects an air of desperate loneliness.

Approaching from the east, the statuary memorial to the war’s nurses emerges from the woodline on the left. Where Lincoln has his majesty, this one has its poignancy. Three female nurses are depicted attending to a mortally wounded serviceman. One examines his wounds. Another cradles his head in her hands, perhaps seeing in the mask of agony a husband, lover, son, brother, or father somewhere far away or long gone. The last stares off into space, searching for salvation from a guardian angel riding a Huey through the jungle, or else the angel of death, blackness inexorably descending to meet the young and the doomed, quick and merciful when all hope is gone. Further along one meets the statues of servicemen, a vantage where the first view of the Wall is offered. The Wall itself is tucked against a hillside. The memory of this terrible war, one realizes, is literally half-buried. Between open air and dark, impenetrable soil stands only this marble valhalla of 58,286 names, each a carved admonishment reminding posterity to never forget them. The statues themselves stare back. These are the survivors, the ones who, through a thousand twisted turns of fate, came back. For each, the curve of a bullet, or a few feet of difference in the placement of a mine would have reversed their fate with that of a comrade who was reduced from man to stenciled name. If Jefferson’s bronze statue eternally eyeing the White House is an implicit rebuke of strong executive power, this smaller exhibition of watchfulness reminds forever of the cruelties of war, and the faceless, senseless twists of fate.

If only these reminders were understood by those who come here. An attempted moment of quiet reflection at this statue is destined for interruption by some cadre of tourists taking their photograph with the statues. I stare off at the Wall this night some three feet away from a cluster of teenagers making pistols with their fingers and smiling. Someone takes a selfie. There is laughter, far too much laughter. From where they derive their amusement, I cannot tell. The spectacle is nothing if not obscene. Everything is a video game now, it seems. War is a game. This is a tourist attraction. Death and mortality surely cannot – surely have never – reached out to snatch away the young, bold, and carefree. Surely not?

Stepping away from these eternal gatekeepers, one begins their journey through the Lost Generation cut down in the Southeast Asia jungle. The black headstone grows ever taller on the left. To the right, an orderly rope barricade. This way, please. Keep off the grass. Tour groups hustle past like so many cattle. I want to stop them. I want to ask them, “do you not realize what this is?” But, I do not stop them, and they move briskly through. Just another tourist attraction. The words on the Wall might as well be the telephone book. I see it differently. Perhaps my age makes this the case. I presently find myself midway through college, plotting the future and guided always by bright visions of a better tomorrow. Great things lie ahead, and I can feel them coming. This realization of my own status in life renders the Wall suddenly, in a crashing wave, heart-wrenching far beyond the reach of any pen to describe. For now, at this way-station on the journey of life, I see not just names, but visual representations of 58,286 sets of hopes and dreams cut down, to be left forever unrealized. Every name was a living, breathing human being. Every one of them laughed, loved, mourned, wept, hoped, dreamt, planned, doubted, feared, and wished for something in the cruel world they briefly inhabited. Full lives lay ahead, great shining hopeful futures snuffed out in jungle mud and thundering artillery. And too, I am aware of my own father’s membership in this, the Lost Generation. He made it, by strokes of fortune avoiding the rampaging hell of Southeast Asia. But what if things had been different? Indeed, we would not be here. I can almost picture some nameless, faceless twenty-year-old much like myself standing in my shoes, staring at our family name, wondering similarly what might have been. The road not taken, indeed. The mirrored finish of the war lends this sort of unreal introspection a violent sense of reality. Am I standing here today, I wonder, all because of the simple fact – a decision made decades ago, by a lone individual – that let Dad get into dental school? How fickle is fate. In the case of my family, its hand was kind. For so many others, it was not. Unlike me, they do not stand here today. And they never will. This way, please. Keep off the grass. Let’s take a selfie. Everything is awesome now. The peace signs on your bumper stickers tell us so.

My eyes settle on a name. They always do, and I never know why. John M. Quinn. Panel 4E, Row 125. A quick internet search pulls him back from the mists of fading history. There he is, crooked grin and all. Born, New York City, the 4th of September, 1942. An Army sergeant, who never saw the second month of 1966. He now rests, I see, just across the Potomac at Arlington. I scroll through the remembrances posted below the online tribute. “Please pray for me as I will you that we may merrily meet in heaven.” That from a former classmate. Reading on, I realize that Quinn was only a year or two removed from being ordained a priest. And then, he was in the Army, and then he was gone. “It seemed so senseless that someone who was going to save souls at one time would be taken away. But maybe that was the Lord’s plan all the time. Rest in Peace, John.” The story of this young man, who never made his twenty-fourth year, plays out over and over and over and over again. This memorial is a living thing. It is human. It is the only posterity of the lost. In the mirrored finish, I see myself. Literally, of course, but figuratively to a far greater degree. Shuffle a few decades about on the world stage and I could have found myself part of a conflict such as this one. Even in my dark and lonely days, there shines that hope for the future, the concept that present hurts heal with time, and the best of things lie ahead. To have this snatched – indeed, stolen – cruelly away in the prime of life reaches beyond my comprehension. Any problems I may have seem somehow petty; small, insignificant. I possess no draft card. No conscription now exists. Wherever I may go, I will decide it. No troop transport flight to the valley of the shadow of death looms large in my future. All credit to those for whom it did. Perhaps I’m not so different from all of those school-kids skipping along behind me. Maybe I cannot understand this either. But, I try. Better to try and fail than to not try at all.

Below the names lie the remembrances. These seem purpose-built to jar one from a lonely reverie. There are the flags; the dog-tags; the remembrances. Some from those who never knew the dead whom they address. And then, the saddest of all, those that did. “I miss you.” I miss you, Daddy. Little brother. Son. Baby. We didn’t think we could live without you. Yet, here we are. Gone, but never forgotten. A marble inscription to some. To others, that last precious symbol of a loved one snatched from the Earth by the incomprehensible forces ever at work on the field of battle. Oh, what might have been? What might have been, what was, and what will never be?

I could stand here forever. Somehow, though, that would be inappropriate. In any event, it will get dark soon. These quiet moments of reflection have to end. Life must go on. It ceased, oh so abruptly for those honored on this black stone. I realize the gift of life here, and the jarring brutality of death in all its forms. And, yet, I must move on. Perhaps this is the best honor for them. Carry on. Keep moving. You have but one life. Live it. Always live it, before it is all too late. Remember them, the Lost Generation, and all they wanted, and never had. As I walk off, a bit of heart stays behind. I have learned so much here this night. If only humanity, too, would read the lessons between the lines of names. If in Washington, go to the Wall, and spend time there. Face your own reflection. Ponder your own life. Remember the meaning of sacrifice, learn the lessons of history, and vow to never repeat them.

The sun sets behind me, as a few lines of music suddenly drift unbidden through my mind.

But they can’t touch me now,And you can’t touch me now,They ain’t gonna do to me what I watched them do to you.So say goodbye, it’s Independence Day,It’s Independence Day, all down the line.Just say goodbye, it’s Independence Day,It’s Independence Day this time.Well say goodbye, it’s Independence Day,It’s Independence Day, all boys must run away.So say goodbye, it’s Independence Day,All men must make their way, come Independence Day.

Author’s Note: The included tributes to John Quinn may be viewed here:The included lyrics are taken from “Independence Day” recorded by Bruce Springsteen on The River in 1980.

The physical act of travel has undergone a remarkable transformation during the past two centuries. It was stifled for millennia by the limits of human mobility. Finally, advances in technology spurred a renaissance, as new forms of transportation were born. Railroads blazed the trail, and then humanity conquered the skies, slipping the surly bonds of Earth for the first time. Even a single century brought incredible progress: in May 1869, the first transcontinental railroad was completed. One hundred years and two months later, man would travel nearly 250,000 miles to the moon. The problems of distance and human endurance were vanquished; still, the definition of travel has grown ever more complex, as the literal act of it has become much simpler.

The physical act of travel has undergone a remarkable transformation during the past two centuries. It was stifled for millennia by the limits of human mobility. Finally, advances in technology spurred a renaissance, as new forms of transportation were born. Railroads blazed the trail, and then humanity conquered the skies, slipping the surly bonds of Earth for the first time. Even a single century brought incredible progress: in May 1869, the first transcontinental railroad was completed. One hundred years and two months later, man would travel nearly 250,000 miles to the moon. The problems of distance and human endurance were vanquished; still, the definition of travel has grown ever more complex, as the literal act of it has become much simpler.